In this section:

- Carter & Cassidy (1998) state dependent memory and forgetting

- Eye Witness Testimony (EWT) and the role of leading questions

- Loftus & Palmer (1974) experiment 1 & experiment 2 – leading verbs and speed estimates – response bias & memory distortion

- The role of post event discussion in EWT.

- Gabbert et al (2003) co-witness vs individual

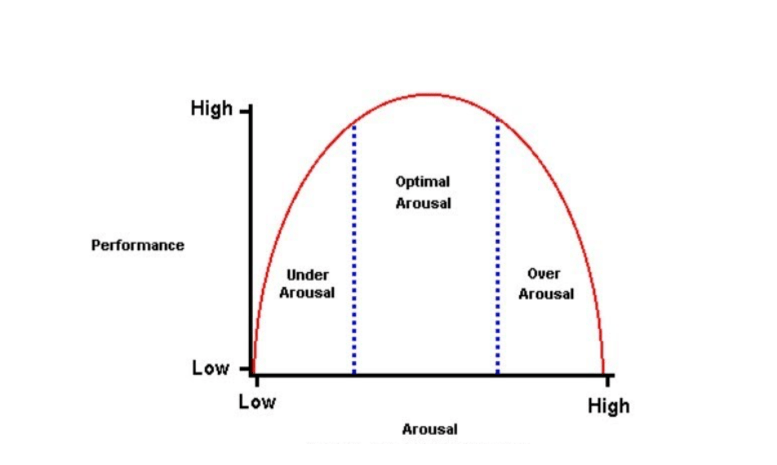

- The inverted U relationship by Yerkes-Dodson.

- How anxiety can decrease accuracy of EWT through the research by Johnson & Scott (1976)

- Deffenbacher et al (2004) application of Yerkes-Dodson law to EWT

- Weapon focus effect as outlined by Loftus.

- Valentine et al (2009) heart rate/anxiety

- How anxiety can increase accuracy of EWT through the research by Cutshall et al (1986)

- Bothwell et al (1987) weakness of anxiety theories – consideration of individual differences

- Cognitive interview (CI), an enhanced cognitive interview (ECI) and a standard interview (SI)

- Fisher & Gieselman (1992) stages of CI: report everything, context reinstatement, narrative reordering and recall from different perspectives

- Fisher (1989) CI more effective than SI

- Fisher (1990) effectiveness of ECI

- Milne & Bull (2002) – usefulness of report everything and context reinstatement

- Kohnken et al (1999) increase in incorrect info in CI

Factors effecting eyewitness testimony: Misleading information

An ‘eyewitness’ is someone who has seen or witnessed a crime, usually present at the time of the incident.

‘Eyewitness Testimony’ = the evidence provided in court by a person who witnessed a crime, with a view to identifying the perpetrator.

Leading questions

A leading question is a question that either by form or content, suggests a desired answer or leads a an individual to believe a desired answer.

Note: the examiners may ask a question using the phrase ‘misleading information’ rather than leading question.

Much of the research in this area has been carried out by Elizabeth Loftus. Loftus has appeared in court as an expert known for studying false, repressed and unreliable memories for clients including the serial killer Ted Bundy, and most recently (Feb 2020) Harvey Weinstein.

Loftus is the co-author of the 1994 book The Myth of Repressed Memory: False Memories and Allegation of Sexual Abuse. In another book, Witness for the Defense, Loftus wrote that in her work for Bundy she seized on “leading and suggestive questions” by investigators and “hesitations and uncertainties on the part of the victim” as signs of muddled memories. Loftus also highlights how law enforcement “can lead people to want to produce details”.

By the way, I highly recommend that you read the books above as wider reading. They are superb!

Loftus and Palmer (1974)

EXPERIMENT 1:

Loftus had a sample of 45 American students recruited via a self-selected sample – advertised at he university – could potentially earn course credit.

All participants were shown the same 7 film clips of different traffic accidents which were originally made as part of a driver safety film.

After each clip participants were given a questionnaire which asked them firstly to describe the accident and then answer a series of questions about the accident.

There was one critical/leading question in the questionnaire: “About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?”

One group was given this question while the other 4 groups were given the verbs “smashed’, ‘collided’, ‘contacted’ or ‘bumped’, instead of ‘hit’.

Results:

Mean speed estimates in mph for the verbs used in the critical/leading question

Smashed 40.8

Collided 39.3

Bumped 38.1

Hit 34.0

Contacted 31.8

Conclusion:

Response bias – The verb used in a question doesn’t influence the memory of the event, but instead influences a participant’s response i.e. the way a question is phrased influences the answer given. The leading question is used as a clue, which leads them to answer in a particular way.

EXPERIMENT 2:

150 students were divided into 3 groups with 50 participants in each group.

All participants were shown a one-minute film which contained a 4-second multiple car crash.

They were then given a questionnaire which asked them to describe the accident and answer a set of questions about the incident.

There was a critical question about speed:

– One group was asked, “About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?”

– Another group was asked, “About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?”

– The third group did not have a question about vehicular speed.

One week later, all participants, without seeing the film again, completed another questionnaire about the accident which contained the further critical question, “Did you see any broken glass – Yes/No?” There had been no broken glass in the original film.

Results:

Speed estimates for the verbs used in the question about speed

Response Smashed Hit Control

Yes 16 7 6

No 34 43 44

Conclusion:

Substitution explanation or Memory distortion – Misleading post event information can distort an individual’s memory. It is proposed that two kinds of information go into our memory for a ‘complex occurrence’. Firstly, the information during the perception of the original event (car crash). Secondly, the post-event information that is gained after the event (leading questions smashed/hit and did you see glass?). Information from the two sources will integrate over time and form a memory that makes sense to us. A false memory is formed.

Post-event Discussion

Post-event discussion is where two people witness a crime and then talk about what happened afterwards. This discussion could lead to inaccurate testimony because they combine information/misinformation from other peoples recollections with their own memories. Details from each account are combined to form a new/false memory.

Gabbert et al (2003)

Gabbert had a sample which consisted of 60 students from the University of Aberdeen and 60 older adults recruited from a local community.

The participants were either tested individually (control group) or in pairs (co-witness group). The participants in the co-witness group were told that they had watched the same video. However, the participants viewed the film from different points of view. This meant that each participant could see elements in the event, that the other could not. For example only one participant could see the title of a book being carried by a woman and only one participant could actually see the girl stealing.

Both participants then discussed what they had seen before individually completing a test of recall.

Gabbert et al. found that 71% of the witnesses in the co-witness group recalled information they had not actually seen and 60% said that the girl was guilty, despite the fact they had not seen her commit a crime. These results highlight the issue of post-event discussion and the powerful effect this can have on the accuracy of eyewitness testimony.

Evaluation

Strengths:

- Applications – Both pieces of research can be implemented into improving eyewitness testimony by training police officers in questioning or by making jurors aware in court rooms so that eye witness experts can be used in a trial.

- Quantitative data – Both pieces of research use quantitative data which increases objectivity and reliability. For example Loftus collected speed estimates. This is a strength because it means that due to the objectivity of quantitative data Loftus can easily see if the numerical data bears any differences in the different verbs that Loftus used in the study with little influence of researcher bias.

- Reliability – Both pieces of research can be considered highly reliable as they used standardised procedures such as having the same video clip of car accidents and asking the same critical question in Loftus, and all participants watching the same footage of the girl stealing and being asked the same questions in the recall part. This is a key strength because it means that extraneous variables are reduced due to the standardised procedures which ensured that the measure was consistent. Therefore the researchers can be more confident that the IV effected the DV.

- Ecological validity – Both studies can be considered to have some level of ecologically valid as parts of the study can be seen to reflect real life. For example Loftus used real life car accidents in the films that the participants observed. This is a strength because if the participant experiences the study in a realistic manner, they may act in a way which better presents how their memory would be influenced in real life, thus increasing the validity.

Weaknesses:

- Individual differences – Research by Loftus and Gabbert does not compare the accuracy of memory recall in terms of their age. Research has suggested that people aged between 18-45 are more accurate in eyewitness testimony than people aged 55-75. Research also tends to use younger people such as university students, therefore, people in the older generation may not be fairly represented.

- Ecological validity – Loftus and Gabbert’s research can be argued as lacking ecological validity. The use of clips in both studies does not recreate the emotion of a real life incident. Therefore, the research may not be valid when generalising memory recall in real situations of crimes of accidents. In addition, when giving real accounts in EWT there are far more consequences compared to in a lab study. Your account could be taken to a court of law, these consequences would not be felt by the participant in a lab study.

- Demand Characteristics and Validity – A lot of the research may suffer with demand characteristics. When participants are asked a question that they don’t know the answer to, they guess, especially if they are asked a yes/no question. You answer in a way that seems the most helpful for the researcher.

- Generalisability – The sample in both studies are unlikely to be truly representative of the population. In the study Loftus only used students to study memory distortion. The participants are less likely to be drivers than the whole population due to their age range. This is a major weakness because their speed estimates might have been less accurate as a result of their lack of experience with cars. This therefore questions the validity of the study as it may have been participant variables that effected speed estimates and not the verbs.

Factors effecting eyewitness testimony: Anxiety

The inverted U relationship or Yerkes-Dodson law

The Inverted–U Theory illustrates the relationship between pressure and performance. Also known as the Yerkes–Dodson Law, it explains how to find the optimum level of positive pressure at which people perform at their best. Too much or too little pressure can lead to decreased performance.

Deffenbacher et al (2004)

Valentine et al (2009)

Valentine et al used an opportunity sample of 56 visitors to the London Dungeon. They wore a heart rate monitor throughout their visit. When they were in the dungeon, a ‘scary person’ stepped out in front of them

Afterwards, they were told the purpose and they gained informed consent, and allowed to withdraw. They then completed a questionnaire to find out their state and trait anxiety levels. Additionally, they were asked to describe the scary person without guessing things they didn’t know.

After this, they were shown a 9-person line up and asked to identify the scary person. They were told that the scary person may or may not be in the lineup and were asked to say if they couldn’t identify the person. They also noted their confidence, as a percentage, that the person they selected was the scary person.

They found that those with lower state anxiety recalled more correct information about the scary person. 17% of those who scored above the median state anxiety correctly identified the scary person compared to 75% in the low anxiety group.

Anxiety Increases accuracy:

Christianson et al (1993)

Cutshall et al (1986)

Investigated the effect of anxiety in a real life shooting that happened in Canada. A shop keeper shot a thief dead. There were 21 witnesses and 13 of them agreed to take part in the study. The follow-up research interviews were carried out 4-5 months after the incident and were compared with the original interviews that were carried out at the time of the shooting. The witnesses were also asked to rate how stressed they felt at the time of the event on a 7 point scale. They were also asked if they had experienced any emotional problems since, such as a lack of sleep or flash backs.

They found that the 13 witnesses who took part in the follow-up interview were accurate in their eyewitness accounts 5 months later. In addition, participants who reported higher levels of stress were the most accurate in comparison to the less stressed participants.

These results refute the weapon focus effect and show that in real life cases of extreme anxiety, the accuracy of eyewitness testimony is improved.

Evaluation

Strengths:

- Ecological validity and Ethical – Research that uses real life eye witness testimony is more reflective of the variety of factors that would play a role in the recollection of events, and is far more ethical, as the researchers themselves have not created the stressful condition.

- Applications – Research that understands how accuracy of eye witness testimony can be hindered, can be useful in trying to educate law systems such as the court room and the police department. If they are more aware as to why eye witness accounts may not be accurate, they can be more mindful of this when considering evidence.

- Individual differences – Some research has focused on how individual differences can effect eye witness testimony. For example, Bothwell et al (1987) tested various participants for their level of neuroticism (how much of worrier they are – anxiety prone personalities). They then witnessed a ‘crime’ and had to identify the culprit from an ID parade. When exposed to low levels of stress the participants high in neuroticism (worriers) tended to out-perform the ones low in neuroticism. However, when exposed to high levels of stress, the outcome was completely reversed with the participants scoring high on neuroticism now performing significantly worse. High stress + High neuroticism = Low recall. This research may have increased validity as it tries to identify how differences in personality effect eye witness testimony. Taking an idiographic approach in anxiety is likely to be more reflective of the wide ranging experiences of anxiety that we feel.

Weaknesses:

- Ecological validity – most research into weapons focus has been lab based. In real life situations there seems to be less impact than research would predict. Studies have found that the presence of a weapon has little impact on accurate identification of culprits in real-life identity parades!

- Validity – studies that use field experiments or case studies lack control. For example Cutshall et al, could not control the effects of post-event discussions. This could have acted as an extraneous variable and therefore it is hard to establish cause and effect.

- Reductionist – The inverted U theory is too simplistic. It does not take into account the combination of factors that could effect testimony, such as previous experiences, individual differences, cognition, behaviour, emotional and physiological effects.

- Demand characteristics – Due to lab studies. participants are likely to work out the aim of the study. Especially in studies where participants are asked to watch a video. It could seem pretty obvious that they will be questioned on what they saw on the video.

- Ethics – Research where anxiety is invoked may raise ethical issues of psychological harm.